Docker

Containerization

The most common way of explaining the role of containers in the DevOps context is to consider where the name originated: from shipping containers. Prior to the standardization of shipping containers, if you wantedto transport goods across the ocean, you would package your cargo in a variety of forms ranging from placing it on pallets, storing it in boxes or barrels, or simply wrapping it in cloth. Loading and unloading goods that arrived packaged in all these different ways was inefficient and error- prone, mainly because There'sno single kind of crane or wheelbarrow that could effectively move all of the cargo.

Compare that haphazard approach to deploying a standardized shipping container where the boat and port operator can work with a single form factor, using standardized equipment and shippers and a single, flexible form of packaging for all of their goods. Historically, the usage of standardized shipping containers unlocked a paradigm shift that reduced costs of global shipping by orders of magnitude. Packaging software in a standardized container that can be run on any system in the same way provides an analogous advancement in capability and efficiency.

The most common way you'll interact with containers is through a software system called Docker. Docker provides a declarative programming language that lets you describe, in a file called Dockerfile, how you want the system set up i.e., what programs need to be installed, what files go where, what dependencies need to exist. Then you build that file into a container image which provides a representation of the entire file system specified by your Dockerfile. That image can then be moved to and run on any other machine with a Docker-compatible container runtime, with the guarantee that it will start in an isolated environment with the exact same files and data, every time.

Container Management Best Practices

Design Containers to Build Once/Run Anywhere

Build the container once (say, in CI) so that it can run in your various environments production, development, etc. By using a single image, you guarantee that exactly the same code with exactly the same setup will transition intact from development to production.

To achieve run-anywhere with your containers, extract any differences between environments to runtime container environmental variables.

These are secrets and configurations like connection strings or hostnames. Alternatively, you can implement an entrypoint script in your image that downloads the necessary configuration and secrets from a central secret store (e.g., Amazon or Google Secret Manager, HashiCorp Vault, etc.) before invoking your application.

An additional benefit to the runtime secret/configuration download strategy is that it's reusable for local development, avoiding the need for developers to ever manually fetch secrets or ask another developer to send them the secret file.

Build Images in CI

In the spirit of reproducibility, I encourage you to build your images using automation, preferably part of continuous integration. is ensures the images are themselves built in a repeatable way.

Use a Hosted Registry

Once you're building container images and moving them around, you'll immediately want to be organized about managing the built images themselves. I recommend tagging each image with a unique value derived from source control, perhaps also with a timestamp (e.g., the git hash of the commit where the image was built), and hosting the image in an image registry. Dockerhub has a private registry product, and all the major cloud platforms also offer hosted image registries.

Many hosted registries will also provide vulnerability scanning and other security features attached to their image registry.

Keep Image Sizes as Small as Possible

Smaller Docker images upload faster from CI, download faster to application servers, and start up faster. The difference between uploading a 50MB image and a 5GB image, from an operational perspective, can be the difference between five seconds to start up a new application server and five minutes. That's five more minutes added to your time to deploy, Mean Time to Recovery/rollback, etc. It may not seem like much, but especially in a hotfix scenario, or when you're managing hundreds of application servers these delays add up and have real business impact.

Dockerfile Best Practices

Every line or command in a Dockerfile generates what is called a layer effectively, a snapshot of the entire image's hard disk. Subsequent layers store deltas between layers. A container image is a collection and composition of those layers.

It follows then that you can minimize the total image size of your container by keeping the individual layers small, and you can minimize a layer by ensuring that each command cleans up any unnecessary data before moving to the next command.

Another technique for keeping image size down is to use multi-stage builds. Multi-stage builds are a bit too complex to describe here, but you can check out Docker's own article on it at ctohb.com/docker.

Container Orchestration

Now that you've got reproducible images of reasonably small size managed in a hosted registry, you have to run and manage them in production. Management includes:

- Downloading and running containers on machines- Setting up secure networking between containers/machines and other services- Configuring service discovery/DNS- Managing configuration and secrets for containers- Automatically scaling services up and down with load- There are two general approaches to container management: hosted and self-managing.

Hosted Container Management

Unless your requirements are unique or your scale is very substantial, you'll get the highest ROI from going with a hosted solution that does the bulk of the work of managing production containers for you. A common and fair criticism of these solutions is that they tend to be considerably more expensive than self-managed options and provide fewer features and more constraints. In exchange you get dramatically less overhead and less complexity, which for most startups is a tradeoff well worth making. Most small teams lack the expertise to effectively self-host, and so self-hosting ends up either requiring a substantial time investment for existing team members or forcing you to hire an expensive DevOps specialist early on. Spending an extra $1,000 a month to avoid either of those problems is likely to deliver very good ROI.

Some common hosted container platforms include Heroku, Google App Engine, Elastic Beanstalk, Google Cloud Run. Vercel is another popular hosted backend solution, though it does not run containers as described here.

Self-Managed/Kubernetes

The most popular self-management solution for containers is called Kubernetes, often abbreviated K8s. Kubernetes is an extremely powerful and flexible, and thus complicated, system. The learning curve is steep, but the benefits and ROI are worthwhile if you're at the point of needing to self-manage your containers.

If you're considering going this route, I strongly advise against learning Kubernetes on the job. Especially for a team leader, it's too much to take on and do well on an ad-hoc basis. Instead, I recommend buying a book on Kubernetes and committing a week or two to reading it and setting up your own sandbox to get up to speed before diving in for a professional project. It's also a good idea to seek out an advisor or mentor who has a good understanding of Kubernetes to act as an accelerator for your learning of the tool.

FROM THE CREATORS OF MS AZURE LINUX TEAM. Docker gives a way to run multiple applications in parallel. Each application runs on its own secure environment, isolated from the main application and from other Docker instances.

Containers

- OS Isolation

- cgroup

- process space

- network space

- Namespace Isolation

- User Container Object

Basics

| Terms | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Platform | the software that makes Docker containers possible |

| Engine | client-server app (CE or Enterprise) |

| Client | handles Docker CLI so you can communicate with the Daemon |

| Daemon | Docker server that manages key things. Docker Daemon is the Docker server that listens for Docker API requests. The Docker Daemon manages images, containers, networks, and volumes. |

| Volumes | persistent data storage |

| Registry | remote image storage |

| Docker Hub | default and largest Docker Registry |

| Repository | collection of Docker images, e.g. Alpine |

| Docker Volumes | are the best way to store the persistent data that your apps consume and create. |

| Docker Image | Images are the immutable master template that is used to pump out containers that are all exactly alike. |

Using Docker for React Native iOS app development provides a consistent and isolated environment for building and testing your app across different development machines. It simplifies the setup process by encapsulating the required dependencies and tools within a Docker container, ensuring consistent builds and reducing environment-related issues.

Scaling

Networking — connect containers together Compose — time saver for multi-container apps Swarm — orchestrates container deployment Services — containers in production

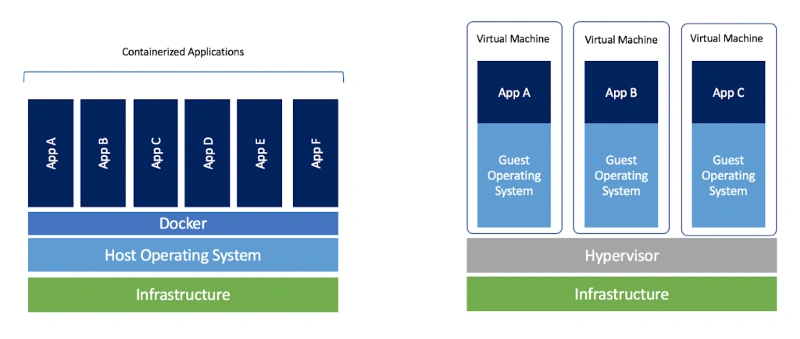

Virtual Machines

(Advantage) Hypervisor Isolation (disadvantage) OS per Application

Virtual machines are the precursors to Docker containers. Virtual machines also isolate an application and its dependencies. However, Docker containers are superior to virtual machines because they take fewer resources, are very portable, and are faster to spin up.

It may look like a virtual machine at first but the functionality is not the same.

Unlike Docker, a virtual machine will include a complete operating system. It will work independently and act like a computer.

Docker will only share the resources of the host machine in order to run its environments.

Dockerfile

A Dockerfile is a file with instructions for how Docker should build your image.

FROM ubuntu 18.04

# Install Dependencies

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| FROM | specifies the base (parent) image. |

| LABEL | provides metadata. Good place to include maintainer info. |

| ENV | sets a persistent environment variable. |

| RUN | runs a command and creates an image layer. Used to install packages into containers. |

| COPY | copies files and directories to the container. |

| ADD | copies files and directories to the container. Can upack local .tar files. |

| CMD | provides a command and arguments for an executing container. Parameters can be overridden. There can be only one CMD. |

| WORKDIR | sets the working directory for the instructions that follow. |

| ARG | defines a variable to pass to Docker at build-time. |

| ENTRYPOINT | provides command and arguments for an executing container. Arguments persist. |

| EXPOSE | exposes a port. |

| VOLUME | creates a directory mount point to access and store persistent data. |